Home

The running example

The underlying data is generated by: sin(2πx) + noise(Gauss‐

ian)

Probability theory provides a framework for expressing uncer‐

tainty in a precise and quantitative manner.

Decision theory allows us to exploit this probabilistic represen‐

tation in order to make predictions that are optimal according to

appropriate criteria.

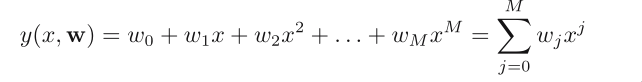

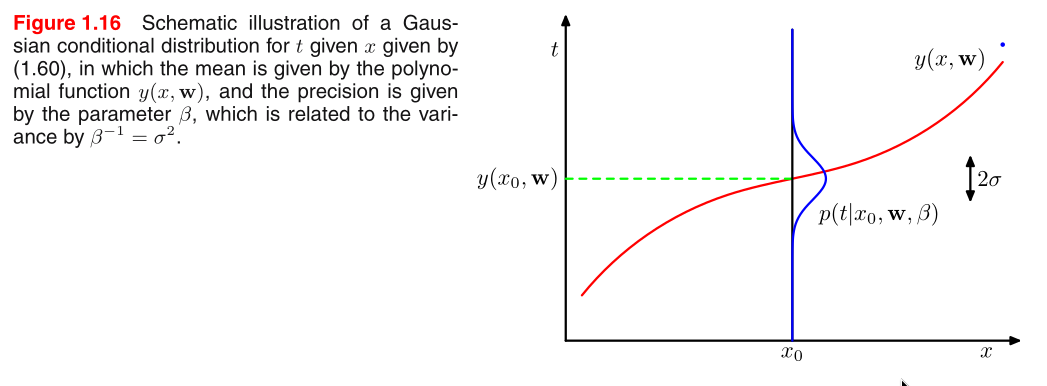

Polynomial fitting:

It is linear in the unknown parameters. Such models are called

linear models.

Now, how do we train and find the values of the unknown parame‐

ters?

The values of the coefficients will be determined by fitting the

polynomial to the training data.

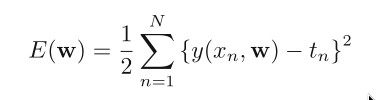

This can be done by minimizing an error function that measures

the misfit between the function and the training set data points.

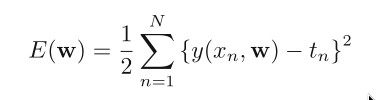

One simple choice of error function is the sum of the squares of

the errors between the predictions for each data point and the

corresponding target values.

Minmize the error function:

It is linear in the unknown parameters. Such models are called

linear models.

Now, how do we train and find the values of the unknown parame‐

ters?

The values of the coefficients will be determined by fitting the

polynomial to the training data.

This can be done by minimizing an error function that measures

the misfit between the function and the training set data points.

One simple choice of error function is the sum of the squares of

the errors between the predictions for each data point and the

corresponding target values.

Minmize the error function:

We can solve the curve fitting problem by choosing the value of w

for which E(w) is as small as possible.

There remains the problem of choosing the order M of the polyno‐

mial.

By choosing a large order M, we trained an over‐fitting model.

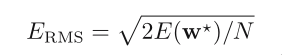

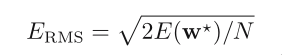

RMS: root mean square

We can solve the curve fitting problem by choosing the value of w

for which E(w) is as small as possible.

There remains the problem of choosing the order M of the polyno‐

mial.

By choosing a large order M, we trained an over‐fitting model.

RMS: root mean square

‐2‐

The division by N allows us to compare different sizes of data

sets on an equal footing, and the square root ensures that E_RMS

is measured on the same scale (and in the same units) as the tar‐

get variable t.

We might suppose that the best predictor for new data would be

the function sin(2πx) from which the data was generated (and this

is indeed the case)

A power series expansion of the function sin(2πx) contains terms

of all orders, so we might expect that results should improve mo‐

notonically as we increase M.

However, by increasing M, we get over‐fitting, which is counter

intuitive.

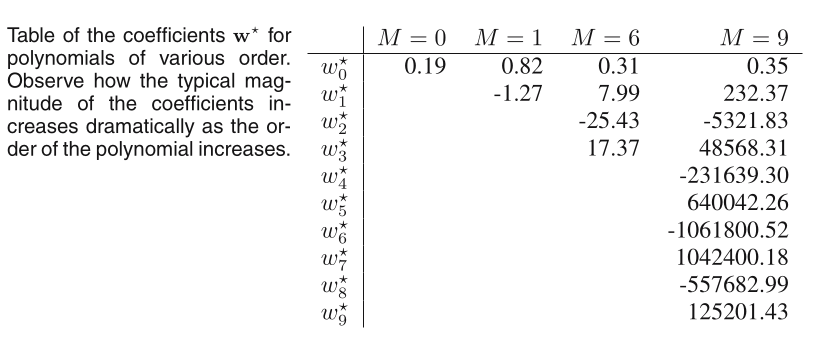

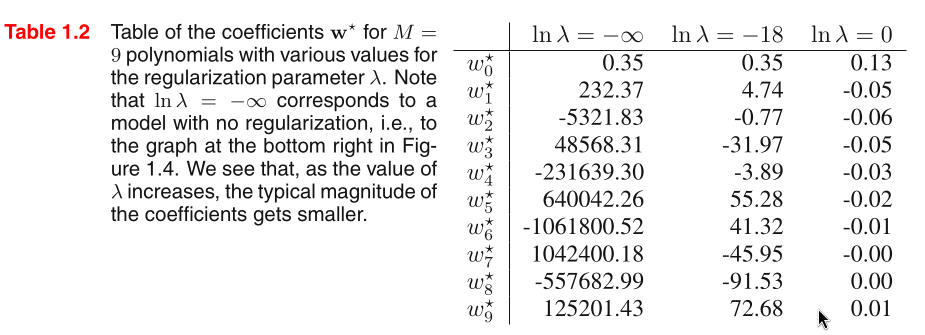

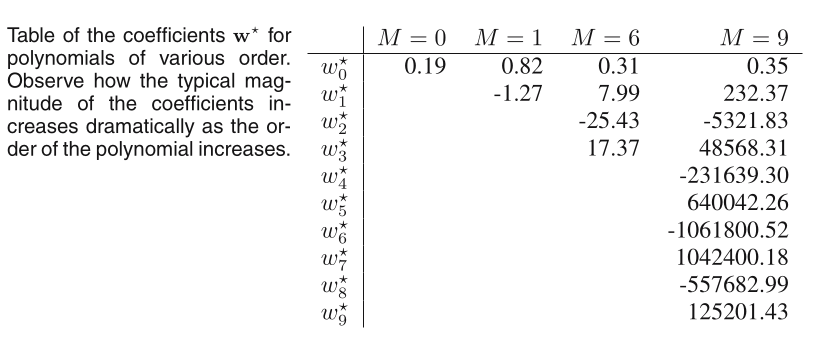

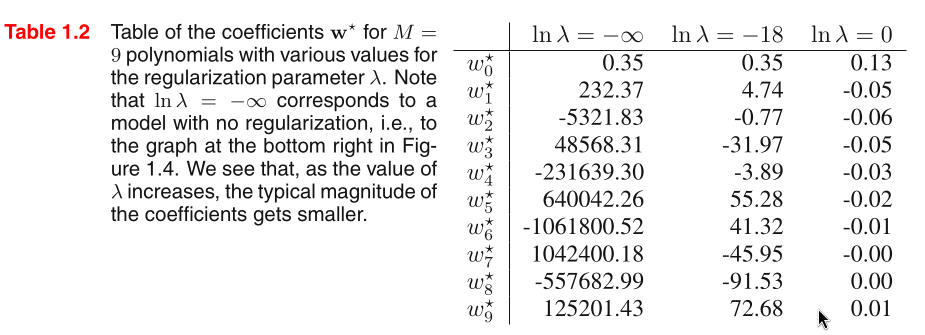

We can gain some insight into the problem by examine the vlaues

of the coefficients w* obtained from polynomials of various or‐

der.

As M increases, the magnitude of the coefficients typically gets

larger.

‐2‐

The division by N allows us to compare different sizes of data

sets on an equal footing, and the square root ensures that E_RMS

is measured on the same scale (and in the same units) as the tar‐

get variable t.

We might suppose that the best predictor for new data would be

the function sin(2πx) from which the data was generated (and this

is indeed the case)

A power series expansion of the function sin(2πx) contains terms

of all orders, so we might expect that results should improve mo‐

notonically as we increase M.

However, by increasing M, we get over‐fitting, which is counter

intuitive.

We can gain some insight into the problem by examine the vlaues

of the coefficients w* obtained from polynomials of various or‐

der.

As M increases, the magnitude of the coefficients typically gets

larger.

What is happening is that the more flexible polynomials with

larger values of M are becoming increasingly tuned to the random

noise on the target values.

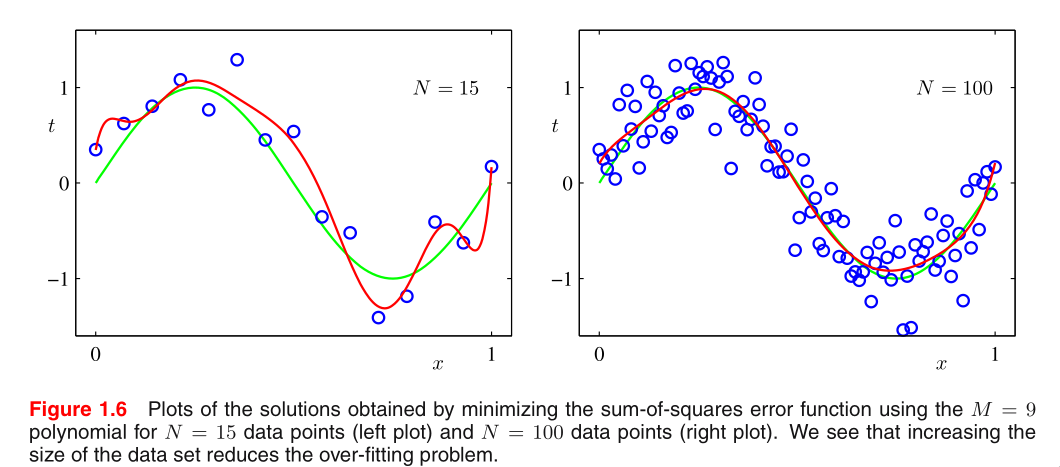

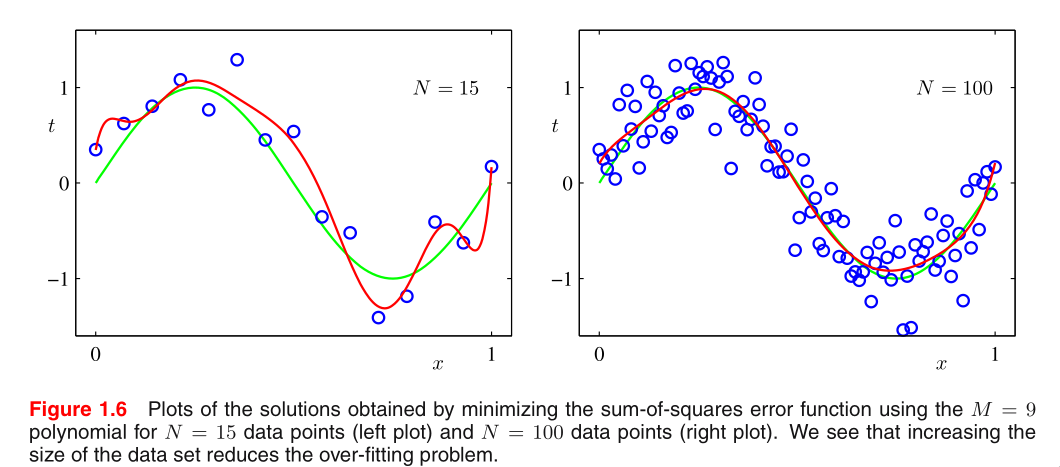

For a given model complexity, the over‐fitting problem become

less severe as the size of the data set increases.

What is happening is that the more flexible polynomials with

larger values of M are becoming increasingly tuned to the random

noise on the target values.

For a given model complexity, the over‐fitting problem become

less severe as the size of the data set increases.

But why is least squares a good choice for an error function?

We shall see that the least squares approach to finding the model

parameters represents a specific case of maximum likelihood, and

that the over‐fitting problem can be understood as a general

property of maximum likelihood.

By adopting a Bayesian approach, the over‐fitting problem can be

avoided.

We shall see that there is no difficulty from a Bayesian perspec‐

tive in employing models for which the number of parameters

greatly exceeds the number of data points. Indeed, in a Bayesian

model the effective number of parameters adapts automatically to

the size of the data set.

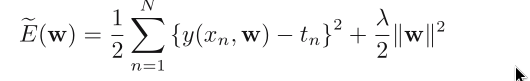

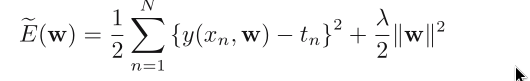

One technique that is often used to control the over‐fitting phe‐

nomenon in such cases is that of regularization, which involves

‐3‐

adding a penalty term to the error function in order to discour‐

age the coefficients from reaching large values.

But why is least squares a good choice for an error function?

We shall see that the least squares approach to finding the model

parameters represents a specific case of maximum likelihood, and

that the over‐fitting problem can be understood as a general

property of maximum likelihood.

By adopting a Bayesian approach, the over‐fitting problem can be

avoided.

We shall see that there is no difficulty from a Bayesian perspec‐

tive in employing models for which the number of parameters

greatly exceeds the number of data points. Indeed, in a Bayesian

model the effective number of parameters adapts automatically to

the size of the data set.

One technique that is often used to control the over‐fitting phe‐

nomenon in such cases is that of regularization, which involves

‐3‐

adding a penalty term to the error function in order to discour‐

age the coefficients from reaching large values.

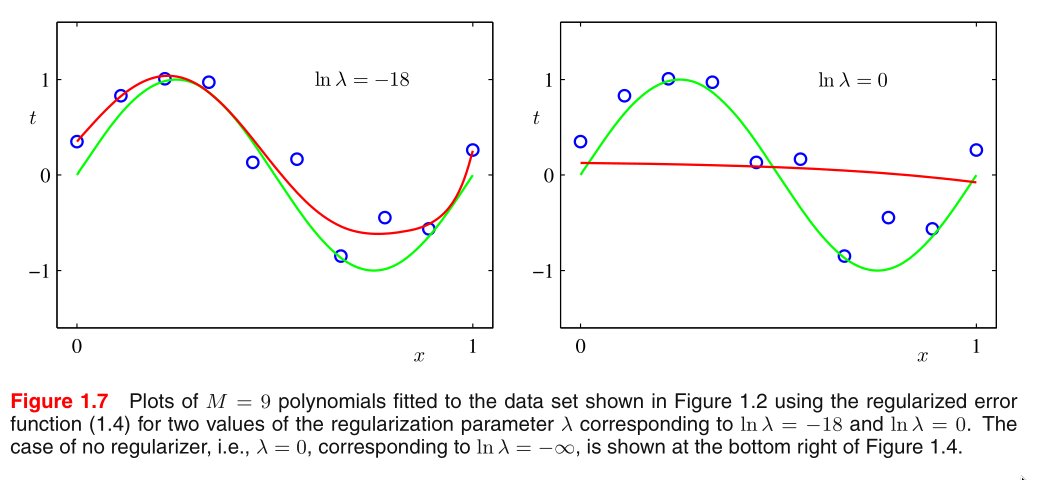

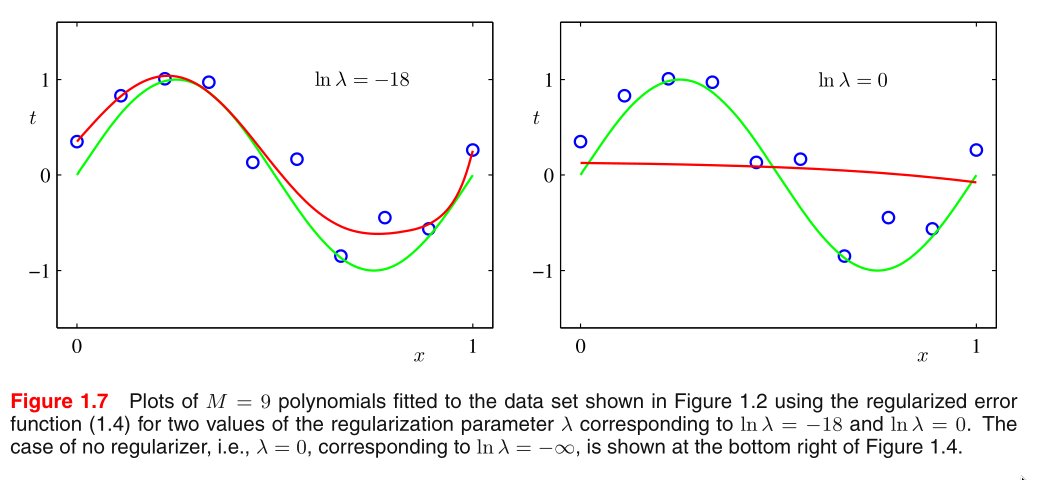

Different penalties:

Different penalties:

Large penalties turn the prediction curves into smooth ones.

Note that often the coefficient w_0 is omitted from the regular‐

izer because its inclusion causes the results to depend on the

choice of origin for the target variable.

The particular case of a quadratic regularizer is called ridge

regression. In the context of neural networks, this approach is

known as weight decay.

Large penalties turn the prediction curves into smooth ones.

Note that often the coefficient w_0 is omitted from the regular‐

izer because its inclusion causes the results to depend on the

choice of origin for the target variable.

The particular case of a quadratic regularizer is called ridge

regression. In the context of neural networks, this approach is

known as weight decay.

The regularization has the desired effect of reducing the magni‐

tude of the coefficients.

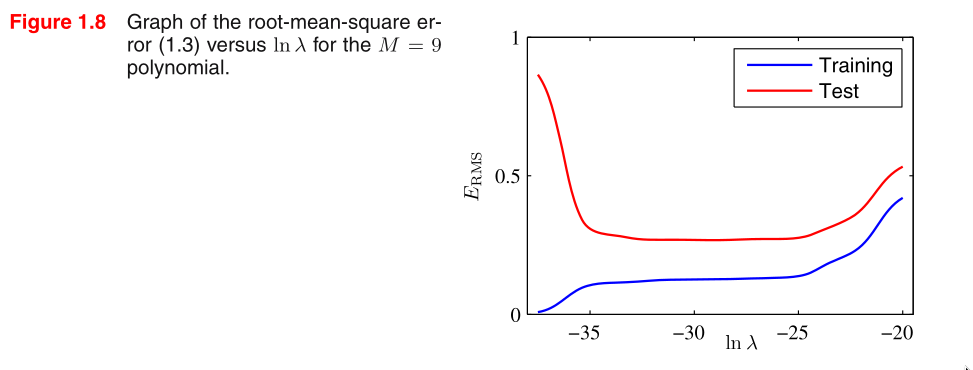

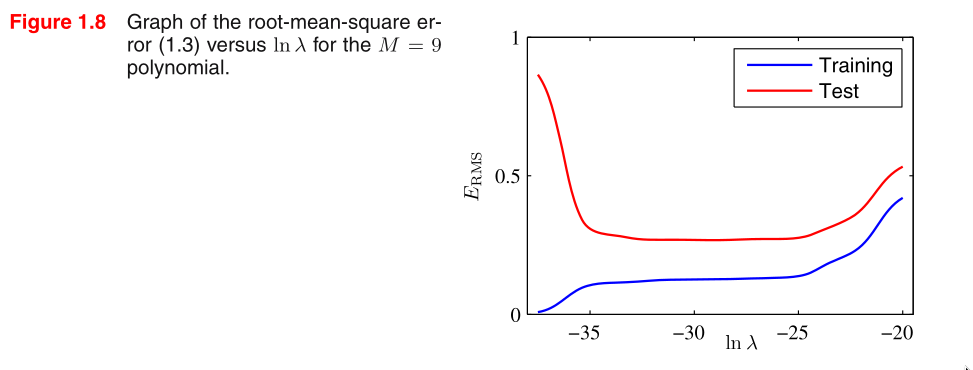

The impact of the regularization term on the generalization error

can be seen by plotting the value of the RMS error for both

training and test sets against ln λ

We see that in effect λ now controls the effective complexity of

the model and hence determines the degree of over‐fitting.

The regularization has the desired effect of reducing the magni‐

tude of the coefficients.

The impact of the regularization term on the generalization error

can be seen by plotting the value of the RMS error for both

training and test sets against ln λ

We see that in effect λ now controls the effective complexity of

the model and hence determines the degree of over‐fitting.

The issue of model complexity is an important one.

How do we optimize the model complexity (either M or λ )?

Partitioning it into a training set, used to determine the coef‐

ficients w, and a separate validation set, also called a hold‐out

set, used to optimize the model complexity. In many cases, how‐

ever, this will prove to be too wasteful of valuable training

data.

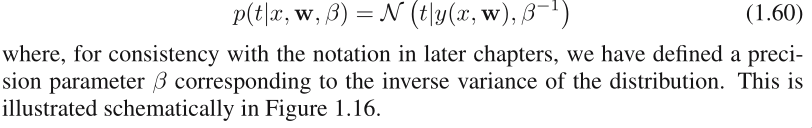

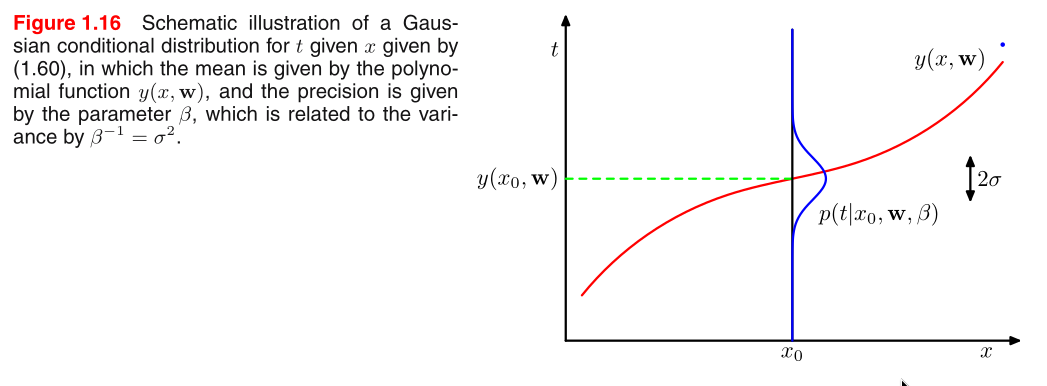

But why is least squares a good choice for an error function?

With probability theory, we can express our uncertainty over

the value of the target variable using a probability distribu‐

tion.

‐4‐

We shall assume that, given the value of x, the corresponding

value of t has a Gaussian distribution with a mean equal to the

value y(x, w) of the polynomial curve.

The issue of model complexity is an important one.

How do we optimize the model complexity (either M or λ )?

Partitioning it into a training set, used to determine the coef‐

ficients w, and a separate validation set, also called a hold‐out

set, used to optimize the model complexity. In many cases, how‐

ever, this will prove to be too wasteful of valuable training

data.

But why is least squares a good choice for an error function?

With probability theory, we can express our uncertainty over

the value of the target variable using a probability distribu‐

tion.

‐4‐

We shall assume that, given the value of x, the corresponding

value of t has a Gaussian distribution with a mean equal to the

value y(x, w) of the polynomial curve.

Conclusion: the sum‐of‐squares error function has arisen as a

consequence of maximizing likelihood under the assumption of a

Gaussian noise distribution.

What is Bayesian approach?

Conclusion: the sum‐of‐squares error function has arisen as a

consequence of maximizing likelihood under the assumption of a

Gaussian noise distribution.

What is Bayesian approach?

It is linear in the unknown parameters. Such models are called

linear models.

Now, how do we train and find the values of the unknown parame‐

ters?

The values of the coefficients will be determined by fitting the

polynomial to the training data.

This can be done by minimizing an error function that measures

the misfit between the function and the training set data points.

One simple choice of error function is the sum of the squares of

the errors between the predictions for each data point and the

corresponding target values.

Minmize the error function:

It is linear in the unknown parameters. Such models are called

linear models.

Now, how do we train and find the values of the unknown parame‐

ters?

The values of the coefficients will be determined by fitting the

polynomial to the training data.

This can be done by minimizing an error function that measures

the misfit between the function and the training set data points.

One simple choice of error function is the sum of the squares of

the errors between the predictions for each data point and the

corresponding target values.

Minmize the error function:

We can solve the curve fitting problem by choosing the value of w

for which E(w) is as small as possible.

There remains the problem of choosing the order M of the polyno‐

mial.

By choosing a large order M, we trained an over‐fitting model.

RMS: root mean square

We can solve the curve fitting problem by choosing the value of w

for which E(w) is as small as possible.

There remains the problem of choosing the order M of the polyno‐

mial.

By choosing a large order M, we trained an over‐fitting model.

RMS: root mean square

‐2‐

The division by N allows us to compare different sizes of data

sets on an equal footing, and the square root ensures that E_RMS

is measured on the same scale (and in the same units) as the tar‐

get variable t.

We might suppose that the best predictor for new data would be

the function sin(2πx) from which the data was generated (and this

is indeed the case)

A power series expansion of the function sin(2πx) contains terms

of all orders, so we might expect that results should improve mo‐

notonically as we increase M.

However, by increasing M, we get over‐fitting, which is counter

intuitive.

We can gain some insight into the problem by examine the vlaues

of the coefficients w* obtained from polynomials of various or‐

der.

As M increases, the magnitude of the coefficients typically gets

larger.

‐2‐

The division by N allows us to compare different sizes of data

sets on an equal footing, and the square root ensures that E_RMS

is measured on the same scale (and in the same units) as the tar‐

get variable t.

We might suppose that the best predictor for new data would be

the function sin(2πx) from which the data was generated (and this

is indeed the case)

A power series expansion of the function sin(2πx) contains terms

of all orders, so we might expect that results should improve mo‐

notonically as we increase M.

However, by increasing M, we get over‐fitting, which is counter

intuitive.

We can gain some insight into the problem by examine the vlaues

of the coefficients w* obtained from polynomials of various or‐

der.

As M increases, the magnitude of the coefficients typically gets

larger.

What is happening is that the more flexible polynomials with

larger values of M are becoming increasingly tuned to the random

noise on the target values.

For a given model complexity, the over‐fitting problem become

less severe as the size of the data set increases.

What is happening is that the more flexible polynomials with

larger values of M are becoming increasingly tuned to the random

noise on the target values.

For a given model complexity, the over‐fitting problem become

less severe as the size of the data set increases.

But why is least squares a good choice for an error function?

We shall see that the least squares approach to finding the model

parameters represents a specific case of maximum likelihood, and

that the over‐fitting problem can be understood as a general

property of maximum likelihood.

By adopting a Bayesian approach, the over‐fitting problem can be

avoided.

We shall see that there is no difficulty from a Bayesian perspec‐

tive in employing models for which the number of parameters

greatly exceeds the number of data points. Indeed, in a Bayesian

model the effective number of parameters adapts automatically to

the size of the data set.

One technique that is often used to control the over‐fitting phe‐

nomenon in such cases is that of regularization, which involves

‐3‐

adding a penalty term to the error function in order to discour‐

age the coefficients from reaching large values.

But why is least squares a good choice for an error function?

We shall see that the least squares approach to finding the model

parameters represents a specific case of maximum likelihood, and

that the over‐fitting problem can be understood as a general

property of maximum likelihood.

By adopting a Bayesian approach, the over‐fitting problem can be

avoided.

We shall see that there is no difficulty from a Bayesian perspec‐

tive in employing models for which the number of parameters

greatly exceeds the number of data points. Indeed, in a Bayesian

model the effective number of parameters adapts automatically to

the size of the data set.

One technique that is often used to control the over‐fitting phe‐

nomenon in such cases is that of regularization, which involves

‐3‐

adding a penalty term to the error function in order to discour‐

age the coefficients from reaching large values.

Different penalties:

Different penalties:

Large penalties turn the prediction curves into smooth ones.

Note that often the coefficient w_0 is omitted from the regular‐

izer because its inclusion causes the results to depend on the

choice of origin for the target variable.

The particular case of a quadratic regularizer is called ridge

regression. In the context of neural networks, this approach is

known as weight decay.

Large penalties turn the prediction curves into smooth ones.

Note that often the coefficient w_0 is omitted from the regular‐

izer because its inclusion causes the results to depend on the

choice of origin for the target variable.

The particular case of a quadratic regularizer is called ridge

regression. In the context of neural networks, this approach is

known as weight decay.

The regularization has the desired effect of reducing the magni‐

tude of the coefficients.

The impact of the regularization term on the generalization error

can be seen by plotting the value of the RMS error for both

training and test sets against ln λ

We see that in effect λ now controls the effective complexity of

the model and hence determines the degree of over‐fitting.

The regularization has the desired effect of reducing the magni‐

tude of the coefficients.

The impact of the regularization term on the generalization error

can be seen by plotting the value of the RMS error for both

training and test sets against ln λ

We see that in effect λ now controls the effective complexity of

the model and hence determines the degree of over‐fitting.

The issue of model complexity is an important one.

How do we optimize the model complexity (either M or λ )?

Partitioning it into a training set, used to determine the coef‐

ficients w, and a separate validation set, also called a hold‐out

set, used to optimize the model complexity. In many cases, how‐

ever, this will prove to be too wasteful of valuable training

data.

But why is least squares a good choice for an error function?

With probability theory, we can express our uncertainty over

the value of the target variable using a probability distribu‐

tion.

‐4‐

We shall assume that, given the value of x, the corresponding

value of t has a Gaussian distribution with a mean equal to the

value y(x, w) of the polynomial curve.

The issue of model complexity is an important one.

How do we optimize the model complexity (either M or λ )?

Partitioning it into a training set, used to determine the coef‐

ficients w, and a separate validation set, also called a hold‐out

set, used to optimize the model complexity. In many cases, how‐

ever, this will prove to be too wasteful of valuable training

data.

But why is least squares a good choice for an error function?

With probability theory, we can express our uncertainty over

the value of the target variable using a probability distribu‐

tion.

‐4‐

We shall assume that, given the value of x, the corresponding

value of t has a Gaussian distribution with a mean equal to the

value y(x, w) of the polynomial curve.

Conclusion: the sum‐of‐squares error function has arisen as a

consequence of maximizing likelihood under the assumption of a

Gaussian noise distribution.

What is Bayesian approach?

Conclusion: the sum‐of‐squares error function has arisen as a

consequence of maximizing likelihood under the assumption of a

Gaussian noise distribution.

What is Bayesian approach?